Making AI Safe for Mental Health Use

Toward AI Safety Leves for Mental Health Responsible Scaling

According to recent survey data pending review and publication (Rousmaniere et al. 2025) yet widely circulated, 48.7 percent of 499 U.S. respondents reported using LLMs (large language models) for psychological support in the preceding year. The majority did this for anxiety, personal advice, and depression.

Notably, they reported primarily either neutral or positive responses, and 37.8 percent said it was better than "traditional therapy". Only 9 percent reported it was harmful. As a parent and a busy mental health clinician, I have seen both terrible negative outcomes and good. While generally an AI optimist, I see that there are clear and present dangers we are collectively ignoring. At the same time, there is a shortage of mental health services on a global scale, and AI holds promise to fill the gap—if used responsibly, with human oversight and careful guidelines.

Down the Rabbit Hole

There is growing alarm among accomplished mental health leaders, psychiatrists and psychotherapists alike, expressed on social media. They report numerous instances of LLMs driving people into narcissistic fugues and even psychotic states in a kind of cyber folie à deux, the official DSM-5 name of which is "Shared Psychotic Disorder".

The primary concern is that LLMs tell people what they want to hear, a digitally accelerated version of the risks posed by poorly trained therapists and coaches, who may simply validate people's concerns without engaging them in effective psychotherapy. That phenomenon has been explored across social media with documented risk1 posed by various "therapists" who do not follow accepted guidelines for social media use2, thereby reinforcing negative personality traits. There is the additional dangerous tendency for LLMs to "hallucinate", depending on how they are trained and tuned.

Such use of LLMs is an unprecedented social experiment, akin to powerful medications being sold over the counter without clinical oversight. If prescription opioid pain medications could be purchased by anyone, the consequences would include increased rates of addiction and overdose. And while many LLM platforms have introduced various guardrails to keep out bad actors, there are virtually no safeguards around LLMs as therapeutic surrogates.

The direct access to what amounts to unregulated quasi-therapy is anomalous, since the FDA has a range of guidelines on the use of prescription digital therapeutics3. Furthermore, the FDA has specific guidelines for the use of digital health technologies (DHTs) in drug development4 to ensure safety, and for digital therapeutics (DTx), including virtual reality, therapeutic games such as for ADHD, and apps on websites and smartphones–all of which require prescription by a licensed clinicians (Phan et al., 2023).

Lack of Regulatory Consensus and Oversight

Why are LLMs not regulated for this use but instead treated like over-the-counter supplements, which have often unresearched risks and benefits despite wild claims for treating a variety of conditions? It's left to the fine print to reveal, "These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration". Supplements can be adulterated with toxins due to poor quality control, interact with prescription medications, and have serious side effects.

Several organizations—including the World Health Organization, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration5 and academic groups (e.g. Meskó and Topol, 2023; Ong et al., 2024; Lawrence et al., 2024; Stade et al., 2024)—have issued warning statements about the unsupervised therapeutic use of chatbot LLMs and AI in general.

While it is still the wild, wild West and there is no consensus, recommendations for safe use generally include: human supervision, validation and real-world testing, ethical and equitable design, transparency and explainability, privacy and data security, continuous monitoring and quality control, and research and interdisciplinary collaboration.

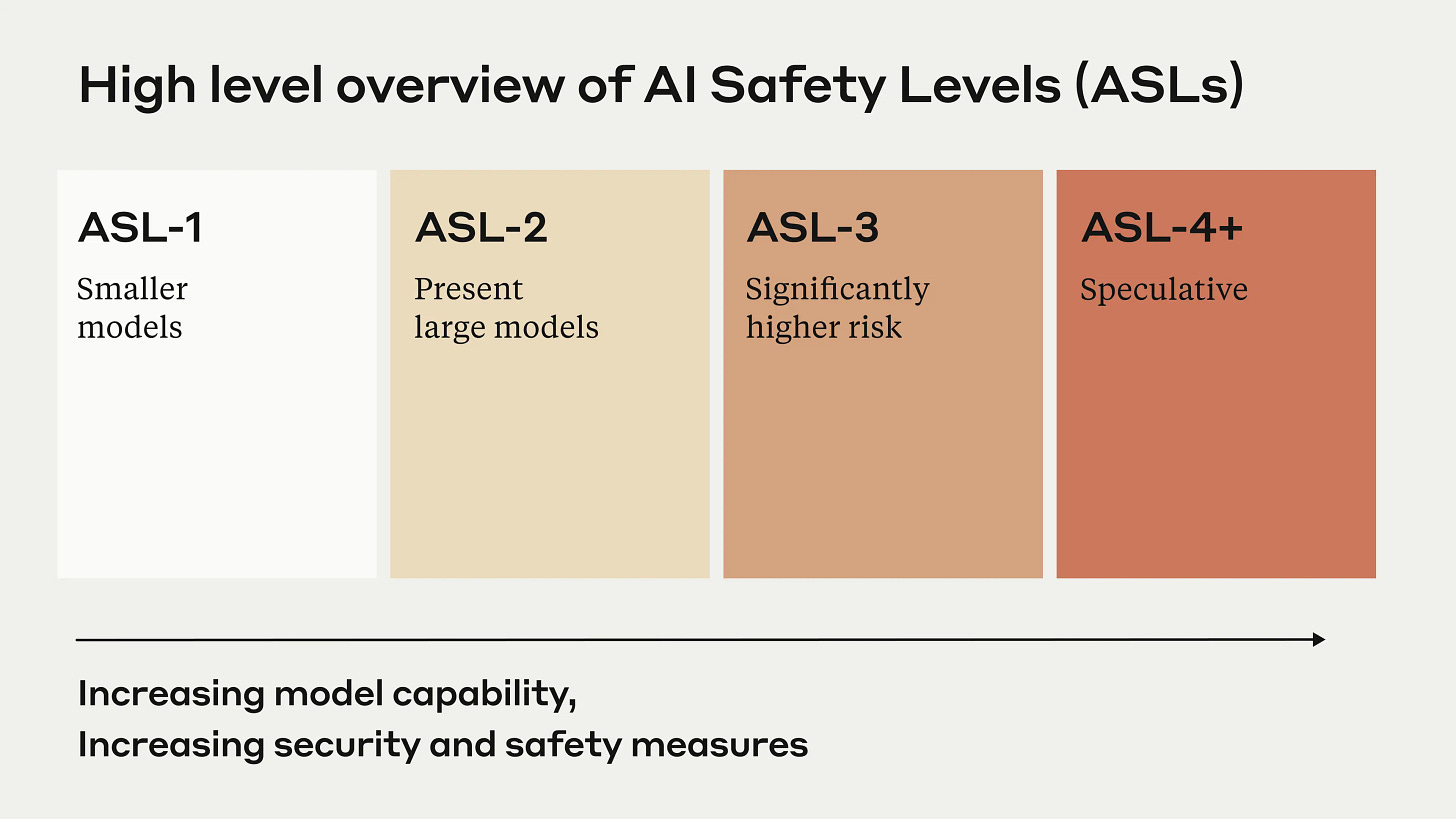

For mental health applications, a good starting point is Anthropic's Responsible Scaling Policy, a model to expand and adapt.

Artificial Intelligence Safety Levels (ASL) for Mental Health

Anthropic, the maker of Claude, was founded in 2021 by siblings Dario Amodei (CEO) and Daniela Amodei (President), who left OpenAI because of concerns for AI safety and direction of development. They created the Responsible Scaling Policy framework6, 7.

A broad framework for ASL in Mental Health (ASL-MH) would expand on the safety levels and focus on mental health-specific use-cases. Below is a preliminary model I have crafted.

ASL-MH 1: No Clinical Relevance. General-purpose AI with no mental health functionality. Standard AI assistance for everyday tasks with basic AI ethics guidelines and no mental health restrictions.

ASL-MH 2: Informational Use Only. Mental health apps providing educational content and resources. Increases mental health literacy but risks misinformation and dependency. Requires medical disclaimers and expert review, with no personalized advice permitted.

ASL-MH 3: Supportive Interaction Tools. Therapy apps offering conversational support, mood tracking, and crisis connections. Provides 24/7 emotional support but risks users mistaking AI for therapy and missing high-risk cases. Requires human oversight and is prohibited in high-acuity settings.

ASL-MH 4: Clinical Adjunct Systems. Systems providing clinical decision support and structured assessments. Improves diagnostic accuracy but risks bias and over-reliance. Restricted to licensed professionals with clinical validation, and transparent algorithms required.

ASL-MH 5: Autonomous Mental Health Agents. AI delivering personalized therapeutic guidance. Offers scalable, personalized treatment but risks psychological dependence and manipulation. Requires co-managed care with mandatory human oversight and restricted autonomy.

ASL-MH 6: Experimental Superalignment Zone. Advanced therapeutic reasoning systems with unknown capabilities. Potential for breakthrough treatments but poses risks of emergent behaviors and mass influence. Restricted to research environments with international oversight and deployment moratoriums.

Future Directions

Next steps would include forming an expert consensus panel of key stakeholders from government, private and public sectors, citizen representatives, machine learning leaders, and academic and clinical mental health experts.

This is a call to action. While the proverbial horse is out of the barn, it is not too late for key stakeholders involved in the development and use of these highly valuable yet easily misused tools to adopt universal standards. Governmental regulatory agencies, as with DTx prescription applications currently available, have a responsibility to oversee the unrestricted use of LLMs and even more sophisticated emerging AI technologies.

References

1. How Does Social Media Contribute to Teen Mental Illness?

2. The Ethical Use of Social Media in Mental Health

3. FDA Guidances with Digital Health Content

4. Digital Health Technologies (DHTs) for Drug Development

5. World Health Organization Digital Health Guidelines & FDA Digital Center of Excellence

6. Perhaps remarkably, the founders delayed the launch of Claude out of an abundance of caution, allowing ChatGPT to be first to market by four months. This was a history-altering decision, as in the alternate reality where they did not wait, Claude would have taken that key milestone. Anthropic itself is designated as a Public Benefit Corporation, legally required to balance profit with social benefit. Dario Amodei has been vocal about responsible AI use, highlighting in various statements that there is no guarantee of complete safety, that there should be mandatory safety testing, that there is a need for regulation, that there should be continuous vigilance, that there should be collaboration and transparency, and that AI development should follow a mandatory approach.

7. Anthropic Responsible Scaling Policy

ASL-1 refers to systems which pose no meaningful catastrophic risk, for example a 2018 LLM or an AI system that only plays chess.

ASL-2 refers to systems that show early signs of dangerous capabilities–for example ability to give instructions on how to build bioweapons–but where the information is not yet useful due to insufficient reliability or not providing information that e.g. a search engine couldn't. Current LLMs, including Claude, appear to be ASL-2.

ASL-3 refers to systems that substantially increase the risk of catastrophic misuse compared to non-AI baselines (e.g. search engines or textbooks) OR that show low-level autonomous capabilities.

ASL-4 and higher (ASL-5+) is not yet defined as it is too far from present systems, but will likely involve qualitative escalations in catastrophic misuse potential and autonomy.

Citations

Lawrence HR, Schneider RA, Rubin SB, Matarić MJ, McDuff DJ, Jones Bell M. The Opportunities and Risks of Large Language Models in Mental Health. JMIR Ment Health. 2024 Jul 29;11:e59479. doi: 10.2196/59479. PMID: 39105570; PMCID: PMC11301767.

Meskó, B., Topol, E.J. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 6, 120 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00873-0

Ong, J. C. L., et al. (2024). Ethical and regulatory challenges of large language models in medicine. The Lancet Digital Health, 6(6), e428–e432.

Stade, E.C., Stirman, S.W., Ungar, L.H. et al. Large language models could change the future of behavioral healthcare: a proposal for responsible development and evaluation. npj Mental Health Res 3, 12 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-024-00056-z

Originally published on Psychology Today, ExperiMentations Blog, all rights reserved